Failure Was An Option...But

Issue #23 of The Two But Rule

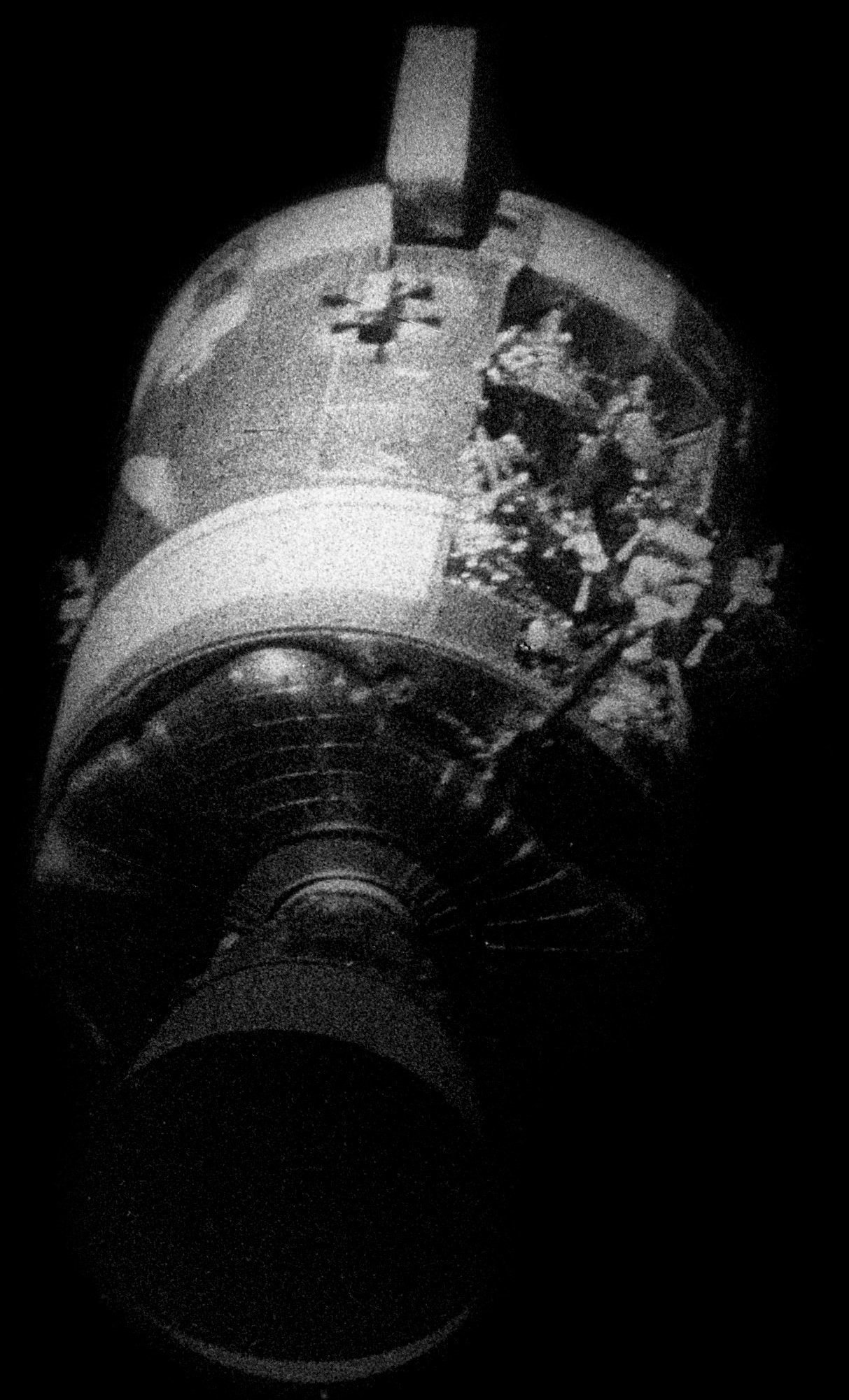

NASA Flight Director Gene Kranz never said, “Failure is not an option.” That was a line delivered by Ed Harris in the 1995 movie, Apollo 13. In fact, during the tense days in April, 1970–when an oxygen tank exploded in the service module taking astronauts Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise to the Moon–failure was’t just an option. It was a likelihood.

What Kranz did say was this: “Let’s solve the problem, people. But let’s not make it any worse by guessing.”

Making Things Worse

Solve the problem. Don’t make it worse. It’s a different way of looking at things than we’ve seen lately in technology, government and society. Gig Economy startups bulldoze whole service sectors while losing vast amounts of money simply papering over the same old problems with new buzzwords. Rash and reactionary government policies sacrifice human decency and common sense to satisfy the demands of an angry political base. Social networks and decentralized financial platforms claim to be about community and inclusion but instead deliver devastating blows to social norms and further concentrate wealth in the hands of elites.

These are the products of a no-buts allowed culture, where the powerful, frustrated with the general pace of change and what they perceive to be seemingly intractable problems, plow ahead with plans. Some believe it’s too hard and time-consuming to understand context, learn how the status quo came to be, or consider the consequences of their actions. As one tech executive put it, “I break things to fix them.” All this underscores a deep misunderstanding we’ve developed about innovation and momentum.

“Move fast and break things,” Facebook’s motto until 2014, set the tone for this approach to ‘disruptive innovation’ that persists to this day. It suggests that deploying new ideas fast without taking constraints into account is better than sitting on your ‘but’ pondering what to do.

Moving Faster With Momentum Thinking

Moving fast sounds great, but it’s worth noting that the Apollo 13 team had no time to spare in saving the crew, and yet they didn’t just move fast and break things. They moved even faster to identify problems, offer ideas, consider new problems presented by those ideas, and manage a complex array of constraints until they had plans that worked. They were engineers and scientists, with plenty of skeptics and contrarians who didn’t hesitate to point out the flaws in a plan. But they also had the mental fortitude and camaraderie as a team to say, over and over, “But that won’t work, BUT it would if…” This is the two-but rule.

For example, when the damaged command module ran out of life support, the three crew members moved into the two-person lunar module, but the CO2 scrubbers were inadequate for the increased load. Left unfixed, the crew would have died of carbon dioxide poisoning. The command module’s scrubbers could handle the job, but they needed to be fitted to the lunar module’s round ports…and they were square. So the ground crew figured out how to fashion a makeshift connector from duct tape, plastic bags and parts from a spacesuit.

They applied the same approach when they discovered a problem with navigation, a serious problem with the power supply, and issues with restarting the dead command module when it was time to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere.

In more than one case, a contrarian viewpoint averted further disaster. An initial plan to use the main engine for a direct return to Earth was scrapped due to the chance of engine damage from the the service module explosion. Later, when they ejected the service module and got a chance to observe the actual damage, it was clear they made the right choice.

In another case, flight controller John Aaron directed the team’s attention from other problems to the spacecraft’s dwindling power supply, convincing them to cut power in time to have enough reserves for re-entry. And later, he threw out the standard playbook and ordered an unorthodox power-up sequence. If he hadn’t, the ship would have run out of its remaining battery power before reaching home.

Don’t Ignore Skeptics, But Insist On The 2nd But

Each time that they found something in a procedure that wouldn’t work, they found a way to make it work or to approach the problem in a new way. Fortunately for the crew, what they didn’t do was a) ignore the skeptics, or b) let skepticism bring them to a halt. For every “but that won’t work” (1But), they found a “but it would work if” (2But), then repeated the cycle, always matching a 1But with a 2But.

Failure, it turns out, is only an option when you stop on an odd-numbered but.

I’ve grown fond of the new phrase, “move fast and fix things.” (Dr. Robert Kozma)